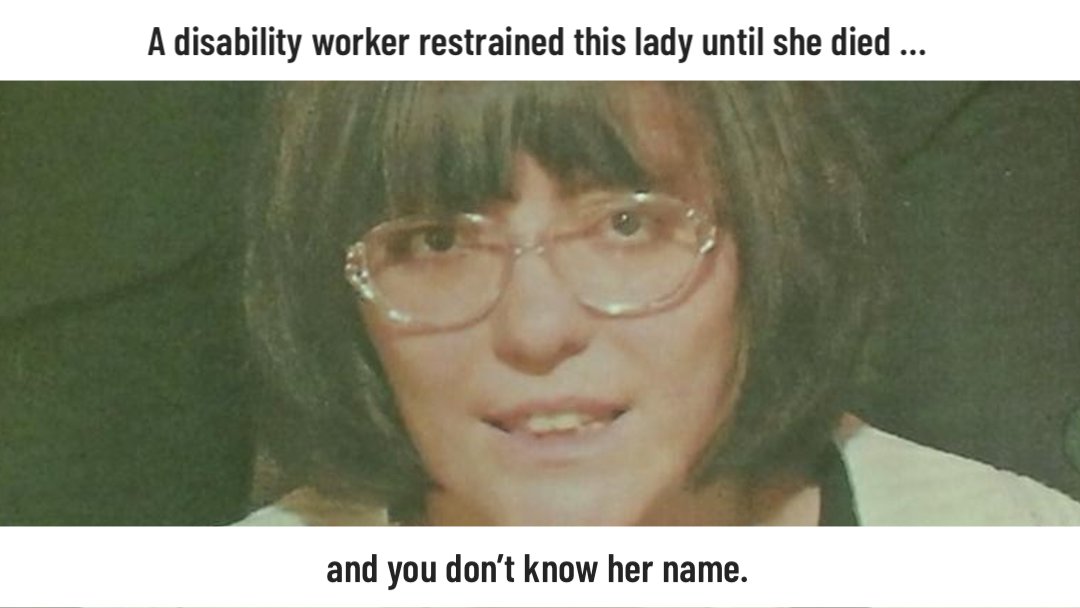

This weekend marks the third anniversary of the death of Heather Roselli. Heather Roselli, who had a developmental disability, died on on June 18th 2017 after being pushed to the ground and held there by the staff of the New York group home where she lived until she died of asphyxia and internal injuries, including broken ribs and a lacerated liver. This attack was prompted by her insistence that she be allowed to call her stepfather. It was Father’s Day.

On the anniversary of her death, the world is rocked with upheaval triggered by the police killing of George Floyd. The similarities are shocking: death by asphyxiation due to an incorrectly performed but theoretically legal restraint. The inciting desire to call her father, echoed in George Floyd’s call for his “Mama”. The lethal use of force by an authority over a devalued member of society, with little consequence (Only one of Heather’s killers will see jail time, and likely for a sentence of less than a year).

But what is most telling is where the similarities end. For while the world has rightly risen up to demand justice for George Floyd, the name of Heather Roselli has been all but forgotten. Why this silence? Why do we not demand justice for Heather? Why do men and women with disabilities continue to suffer the highest rates of every kind of abuse? Why do they continue to die in silence at the hands of their caregivers?

The answer, as in so many of the injustices that wrack the disability community, lies in isolation. Heather Roselli lived and died with only her paid support workers as witnesses. They and they alone were the arbiters of her days, and they proved to be terribly and tragically unworthy of the task. George Floyd had friends and allies, in his personal life, in his faith community, and eventually in government and in the media. These alliances came too late to save him, but they may have at least assured he did not die in vain.

Heather Roselli died as she lived, with only the state to guarantee her value and safety, a role it failed utterly to provide. She had called emergencies services to express her fear that she was going to be killed there, fears that were dismissed. She had no allies but her family, who she was killed for trying to contact. George Floyd was known by many, and because he was known by many, he was loved by many. Because he was loved by many, and they are loved by many, the many have risen up. But Heather Roselli, though loved by those who knew her, was known by few, and is even now being forgotten.

A life of isolation in care is not how life is meant to be lived. It is not only a sad and lonely way to live, but as Heather’s case shows us, it is not even safe. So much of the work we do is in the name of safety, but we have neglected the most important factor in protecting a vulnerable person: a robust and vocal community of natural relationships.

A person who has difficulty advocating for themselves needs witnesses. They need advocates. They need friends with voices that will be heard and listened to. This is why our most important role as paid caregivers is to make ourselves unnecessary. We must not be indispensable. We must be a necessary evil, a crutch until the bone heals. We must be the bridge that those in our care cross out into the real world, where they may be met and come to be cared for, to become friends, to become beloved. For if they are known, they will be loved, and if they are loved they will be safe. They will be missed when they don’t show up at work or at church. Their bruises will be seen and asked about. Their cries for help will be heard, and answered, before it is too late.

Perhaps the most disturbing thing about Heather Roselli’s death remains how little it is known. Almost no one, even among the professionals of the field that killed her, knows her name, though she died only three years ago. What is forgotten is repeated. The walls of a group home are soundproof. It is a place of muffled silence and muted tones, and what is not shouted is not heard at all. We must shout the name of Heather Roselli. We must write it on our hands and brand it on our hearts. And in Heather’s name we must help those we support in breaking down the invisible walls that still surround the group home, that keep those that live there from knowing and being known, from loving and from being loved.

Mike Bonikowsky