A disability support worker shared these words with me and it is one of the most beautiful, insightful and compelling pieces I have ever read.

Ben

Founder | Open Future Learning

Each morning since the pandemic began, I leave my home and drive down the empty highway to the location where I work. I enter the home, sanitize my hands, and greet the five men who live there. Each morning, their expressions and vocalizations are a little more anxious and a little more intense than when I left them previous afternoon. Each morning, I answer their questions: Can we go out today? No, I’m sorry, we can’t. When can we go out again? We just have to take it one day at a time. Why can’t we? Because we could get sick. Is it just us? No. It’s the entire human race. Each morning they respond with a little more resignation, and a little more despair. We settle in for another day of shelter-in-place.

We follow the rules and stay home. We forgo our regular routines and entertainment. The bowling trips, the painting classes, and karaoke at the day program are cancelled. Dwain, whose mental health is closely linked to a stable schedule and his twice-daily bus rides to the local Wal-Mart, is finding the days particularly difficult. When it feels like the walls are beginning to close in, we pile into the van for long drives through the silent countryside of early spring. Gas is cheap. Until this week, we risked the Tim Horton’s drive-through and cradle gently our totemic double-doubles, sipping this rare elixir of normalcy. Together, we watch the live news broadcasts, Trudeau on his porch.

At first I was reluctant to have the news on, worried it might prompt anxiety – for all of us. But when I’d ask what they wanted to watch, their answer was always “the news”. They appreciate keeping up with the latest updates. While it might seem kinder to keep people “in the dark,” respecting choice and self-determination is all the more crucial in times when our options seem so limited. This is their home, not mine. They are adults, so it does not make sense to simply follow the protocols I keep with my children. Similarly, dignity demands that considerate honesty must come before my own desire for a sheltered and calm working environment. We are, after all, truly all in this together.

As we hear announcers share the rising numbers, we try not to think about what an outbreak would mean in this small split-level residence, home to five men of advancing age and already-compromised immunity. We wash our hands again. We stay home some more. We stop risking the drive-through, make our coffee at home, drink it together while we watch the news.

I am afraid. I am afraid for them, but also for me, and for my family. But they are not. In many ways, COVID-19 has not disrupted their lives to the extent it has mine. They are now old men, tough and wise, who came of age in the crucible of the institutions. They have known hardship I can’t imagine. They have friends in the unmarked grave behind Huronia, and do not fear death as I do. They have lost more than I can understand and have lived through much grief – along with joy and celebration. Though not of their own choosing, social isolation is often not a new experience for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. These men, despite their depths of hard-won wisdom and delightful companionship, are well-accustomed to strangers keeping their distance in public places. The conditions we ironically bemoan on social media are barely distinguishable from how they have spent most of the days of their lives. They are old pros at quarantine, and they are teaching me.

My shift ends. I gratefully wash my hands and guiltily break the quarantine, to drive through a numbed town that has lost its freedom. The parks are empty, and the bars and the movie theatres are closed. For the first time, the rest of are learning the taste of institutional living. It is our liberties that have been curtailed, our habits that are being judged, our behaviour that must conform now to programs designed by others. All homes are experiencing increased legislation, restricted freedoms, and pressure to act and behave in certain ways. Throughout history, these demands we now face have too-often been the experience of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. I hope that I – that we – can bear these conditions with half the grace and humour that these men have for so many years. Now we do so to protect vulnerable people from the coronavirus. In the past, vulnerable people have often been asked to act and behave in certain ways only to protect the status quo.

Back at my own home, I find myself without so many of the social connections that add meaning and fulfillment to my life. I taste the marginalization that is part of the daily experience of so many people. We have so much to learn from one another. I am just now learning what many others have been training for their whole life: that when our work is taken from us, when our hands fall still, and when our distractions fail us, we are left with what matters most. We come face-to-face with ourselves, and those who are closest to us. So let’s be good to one another. Let’s be kind and patient. Let’s have grace for lack of social skills, for poorly chosen words, and for tempers lost. Let’s share the television remote and swear at missing puzzle pieces together. Let’s care for one another and be grateful that this isolation is not forever. It is an act of love for a broken world. And when these quarantines end and we once again find it easy to take our casual gatherings for granted, let’s remember Dwain and others for whom “social distancing” has too often been an unchosen reality of marginalization. Let’s stay home together. And when the time comes, let’s leave our homes together as well.

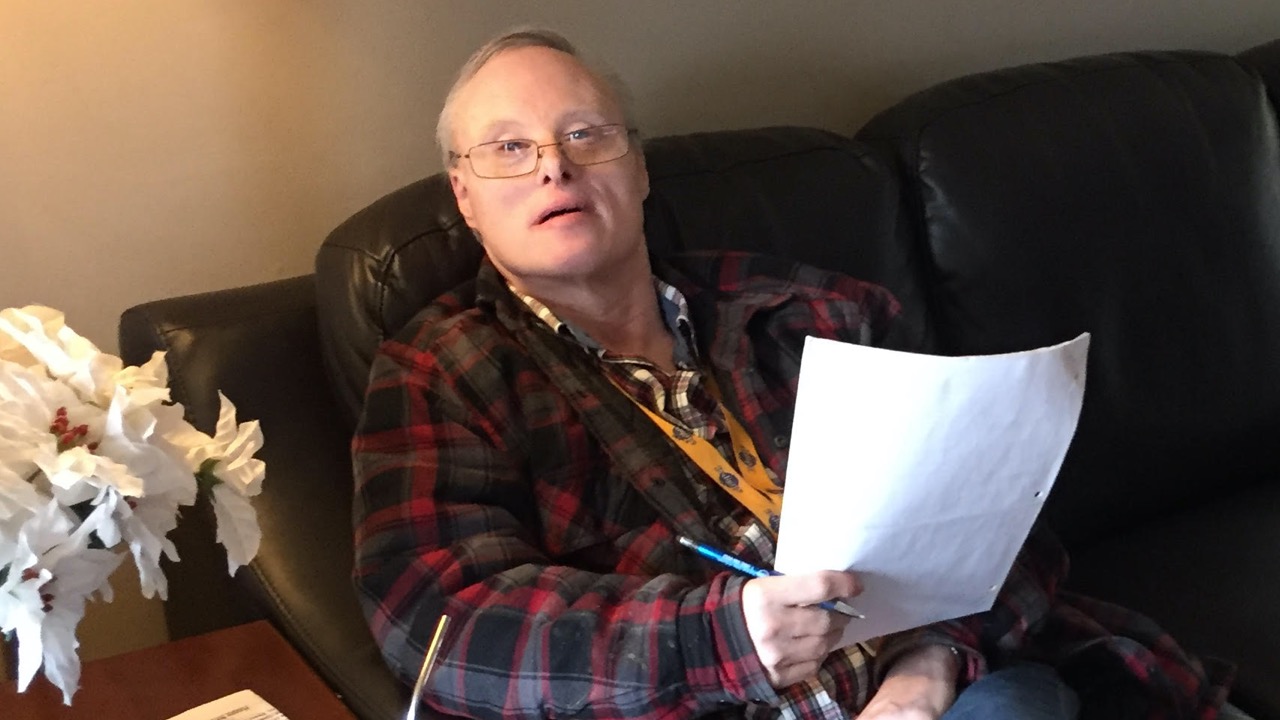

By Mike Bonikowsky

Mike Bonikowsky lives and works in Dufferin County, Ontario. He is a direct support professional with the local Association for Community Living and spends the rest of his time raising two young children. He has been living and working men and women with developmental disabilities since 2007.